The People's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (PMMWR) - October 28, 2025 / No. 1 - Measles elimination status in the US

Snapshot review of the current measles (Rubeola) elimination status in the United States — United States, 2025

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

In 1978, the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set the goal to eliminate measles from the nation by 1982.

Elimination of disease is defined as a reduction to zero of the incidence of a specified disease in a defined geographic area (i.e., the US) as a result of deliberate efforts; continued intervention measures are required (i.e., continuous vaccination). Example: neonatal tetanus in the US.

The eradication of disease is another phrase that is often misused to mean local elimination. The eradication of disease is defined as “permanent reduction to zero of the worldwide incidence of infection caused by a specific agent as a result of deliberate efforts; intervention measures are no longer needed.” Example: smallpox.

Although the CDC did not meet its goal, the widespread uptake of the measles vaccine (the combined measles, mumps, rubella, “MMR,” vaccine was introduced in the US in 1971) dramatically decreased measles disease rates. For example, in 1981, the number of reported measles cases was 80% less than the previous year. Despite this progress, several measles outbreaks in 1989 among vaccinated school children led the CDC’s top vaccine panel, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) to recommend a second dose of the MMR vaccine for children. As a result of this recommendation, as well as increased first-dose MMR vaccine coverage, reported measles cases dropped even more.

The estimated effectiveness of two doses of a measles-containing vaccine to prevent infection is 97%. CDC currently recommends children receive their first measles dose between 12 and 15 months of age, and the second dose between four and six years of age, prior to entering the school system. Measles vaccines in general (beyond the common combined MMR, such the single measles vaccine) have been available in the US since 1963 and are safe and effective at protecting against illness as well as infection and transmission of the virus. Currently, the most common measles-containing vaccine remains to be the MMR vaccine.

In epidemiology, it is estimated that when greater than 95% (>95%) of the population has immunity to measles (via vaccination or previous infection), herd immunity is reached. This means that measles transmission is interrupted and large outbreaks (greater than 50 outbreak-associated cases, >50 cases) will not happen. Thus, at least 95% coverage with two doses of the measles vaccine is often the goal for immunization campaigns and is the current Healthy People 2030 target in the US.

Unfortunately, US measles vaccination rates among school children have been on the decline in recent years. The national vaccination rate fell from 95% in 2019 to 92% in 2023, with a recent (June 2025) county-level analysis from Johns Hopkins University (JHU) showing that out of 2,066 counties studies, 1,614 counties (78%) reported drops in vaccinations. In this dataset, JHU researchers found the average county-level vaccination rate fell from 93.92% pre-pandemic to 91.26% post-pandemic—an average decline of 2.67%, moving us further away from the 95% herd immunity threshold. This coverage varies significantly across states, ranging from as low as 79.6% in Idaho to 98.3% in West Virginia for the 2023-2024 school year. Currently in 2025, 92% of reported measles cases occurred in unvaccinated people.

Measles was declared eliminated from the US in 2000.

The basic definition of elimination for measles in the US (a more extensive definition and benchmarks are described later in this article) is the absence of:

large outbreaks (>50 outbreak-associated cases) and;

continuous, uncontrolled domestic transmission, spread of disease, for greater than 12 months (>12 months)

The verification of elimination status was first done through an internal CDC and external expert review, comparing against pre-set benchmarks. The CDC’s National Immunization Program officially declared measles eliminated in the US in March 2000. An effort was also taken in 2011 by CDC to have external experts re-verify US measles elimination status. The effort resulted in an agreement that measles elimination still applied.

The US continually to reviews measles elimination status, in particular through an external expert committee called the US National Sustainability Committee for the Elimination of Measles, Rubella, and Congenital Rubella Syndrome. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) also monitors elimination status for the Americas. PAHO meets regularly to review evidence and issue reports on the measles elimination status of PAHO member states. The US has consistently received a “sustained elimination” status, including in PAHO’s most recent November 2024 report.

25 years after the historic 2000 accomplishment, the US has reported more cases of measles, 1,618 confirmed cases as of October 21st, this year than any year since 1992 (end of year total cases was 2,200). Only 23 of these cases were reported among international visitors to the US, which suggests that the vast majority of cases have resulted from domestic transmission.

Measles outbreaks have been reported in 41 states. 43 outbreaks (cumulative number of measles outbreaks reported by CDC, defined as three or more related cases, >3 cases) have occurred this year in the US. Of this year’s 43 outbreaks, 87% of confirmed cases (1401/1648) are outbreak-associated, meaning outbreaks are driving the cases. In comparison, only 16 outbreaks were reported in 2024, 69% of which (198/285) were outbreak-associated.

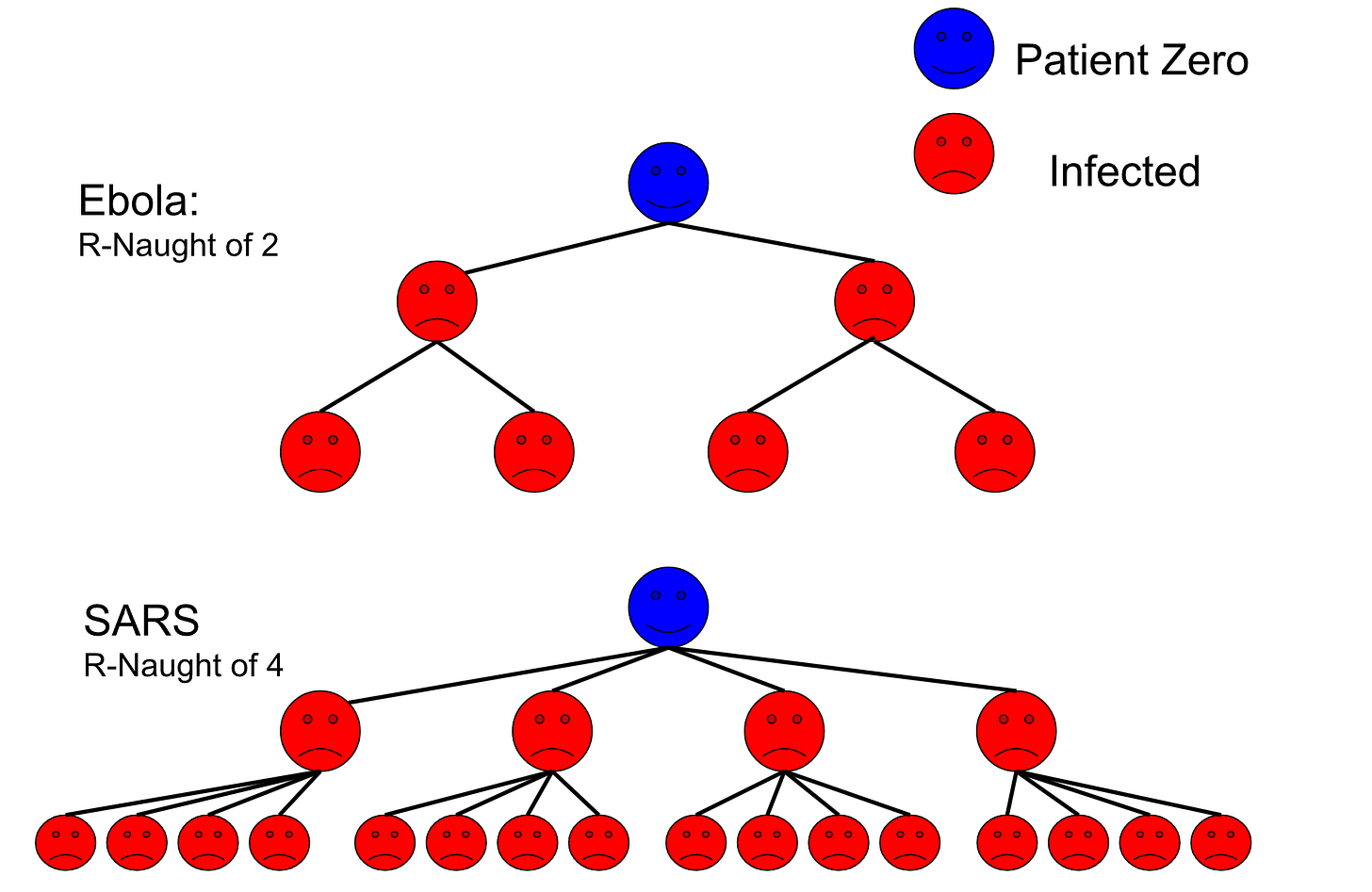

Outbreak-associated cases of measles, especially in an increasingly vaccine- and public health-skeptical population, makes sense as measles is one of the most contagious diseases in the world. Measles’ basic reproduction number (R0), or the estimated average number of measles cases resulting from one case in a population with no prior immunity, is 12 to 18.

Although the majority of measles infections are not severe, health complications can occur in approximately 30% of cases (20%, or 1 in 5 people with measles will be hospitalized). Additionally, 1 to 3 out of 1,000 people will measles will die. The risk for severe outcomes is higher for babies, young children, and immunocompromised people. Of the 1,618 confirmed measles cases as of October 21, 2025, 198 (12%) of cases were hospitalized and three deaths have occurred. Beyond the risk of infection itself, measles can also have long-term impacts on the immune system that may leave the infected person (especially a child) more susceptible to negative outcomes from other, future infections. Those who recover from measles infection generally develop long-term immunity to it.

State and local health departments play leading roles in measles prevention and response work, but rely on funding and other support from the federal government (such as collaboration with staff at HHS and CDC). This funding and support has been devastated by staffing decreases and funding cuts executed by the current administration. Additionally, increased skepticism among the public about the safety and effectiveness of measles vaccines, driven by non-evidence-based rhetoric and policies (lack of or decreased access to quality and affordable education and healthcare), and an overall increased distrust of health officials has led to lower vaccination rates.

The US is not the only country facing a large number of measles cases and outbreaks in 2025. Mexico (4,645 confirmed cases as of writing) and Canada (5,090 confirmed cases) have also battled large outbreaks this year. Just like the US, these outbreaks are primarily located in communities with low vaccination rates. In fact, Canada is likely to lose its measles elimination status next month — sooner than the US — as the country has now (as of late October 2025) exceeded the 12-month observation window for sustained domestic transmission. PAHO will review Canada’s elimination status next month.

Through October of this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that the total confirmed measles cases globally is 177,469. Outside of the Americas, countries with the highest number of measles cases are: Yemen (19,420), Pakistan (13,227), and India (10,368). Higher global circulation of measles means an increased risk for international travel-acquired cases to the US, which in turn can lead to more domestic outbreaks.

What is added by this report?

In this edition of the People’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (PMMWR), I argue that if current trends hold through the rest of the year 2025, the US may plausibly lose its measles elimination status in early 2026, based on prior benchmarks and definitions.

What are the implications for public health practice?

US measles elimination was a significant public health achievement. US measles elimination was made possible by consistent investments in vaccination efforts; disease prevention; control and response; and a societal commitment to a goal.

US measles elimination status is currently at risk and may be rescinded after 2025 in early 2026. Losing measles elimination status would signify that the aforementioned societal commitment to measles prevention and control no longer exists in the US. Additionally, the loss of US measles elimination status would be a harbinger for a future in which measles is endemic (endemic disease is defined as “the constant presence of a disease or infectious agent within a given geographic area or population group; may also refer to the usual prevalence of a given disease within such area or group”) to the US and large outbreaks and sustained transmission are normalized. This future would mean more hospitalizations and deaths, particularly among children, from a disease that is preventable.

Other implications for public health practice might be schools and daycares having to determine whether to close their schools to reduce transmission in the event of an outbreak. To protect from disease, this can be necessary, but prevention (i.e., meeting the herd immunity threshold via >95% childhood vaccination coverage) would have eliminated the existence of such choices, which themselves impact the mental health and finances of students, parents, and teachers. The societal costs of measles outbreaks are high and regular outbreaks would further strain our weakened public health systems in the US.

I recommend a reversal of cuts in staffing and funding for local, state, and federal public health departments, as well as Medicaid, Medicare, and threats to Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies (i.e., reversing of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA)’s stricter verification requirements for premium tax credits, which may end automatic re-enrollment for many and require manual verification for new enrollees); a societal re-dedication to elimination and vaccination campaigns dedicated to achieving the >95% two-dose measles vaccination herd immunity threshold goal; and increased health education on measles and vaccination. I additionally recommend the resignation of RFK Jr. from his position as HHS Secretary for his promotion of misinformation about measles and vaccines.

If US measles elimination status is rescinded after 2025, in early 2026, I recommend the default re-observation of 12-months’ data following the recension, during which public health interventions that have previously been successful are used such as: declaring public health emergencies in affected areas; vaccination mandates for public spaces and institutions, i.e., schools, which includes informed consent; closing of affected schools until cases subside; fines for parents not vaccinating children against measles prior to school enrollment and attendance; and limitations to school attendance based on vaccination status.

Methods

Full definition and benchmarks for US measles elimination

Although I provided a basic definition of US measles elimination in this article’s summary, I provide additional definitions and benchmarks in this article and compare the first 10 months of 2025 data to develop conclusions regarding the measles elimination status.

Hypotheses

H1: US measles elimination status in the US may plausibly be rescinded, based on previous definitions and benchmarks, after January 17th, 2026.

(Null) H0: US measles elimination status in the US may not plausibly be rescinded, based on previous definitions and benchmarks, after January 17th, 2026.

Per the guidelines developed by the US and other PAHO members states, measles elimination is defined at a basic level as:

Interruption of endemic measles virus transmission for a period greater than or equal to 12 months, in the presence of high-quality of surveillance.

As previously mentioned, conversely measles is considered endemic in a given area is continuous, sustained transmission occurs over a 12-month period.

In the process of reviewing US measles elimination status, CDC and external experts use several epidemiologic and programmatic indicators, including: measles cases and transmission patterns, public health measures and response capabilities, and vaccination rates, to determine if endemic measles transmission has been “interrupted” and whether surveillance is “high-quality.”

Application of US measles elimination definition and benchmarks for assessment of health data from the 2001 to 2011 study period

When the external experts re-assess and re-verify measles elimination in 2011, they looked at data from the decade of 2001 to 2011. In their review, they used the following lines of evidence to determine if endemic measles virus transmission was interrupted in the presence of high quality surveillance (i.e., US measles elimination, summary credit goes to KFF):

There were fewer than one reported measles cases per 10 million population;

The majority (>50%) of measles cases were imported and most imported cases did not lead to further US spread — only 40% of cases were imported over the study period;

The number and size of measles outbreaks over that period were small (small outbreak defined by less than 5 cases): a total of 64 outbreaks (median 4 outbreaks/year), with a median outbreak size of 6 cases. Only 16 outbreaks included 10 or more cases;

Measles vaccination rates among children were sustained at high levels (>95%) over the study period, with no significant differences in coverage by race/ethnicity;

Data from national surveys indicated that population immunity to measles was above the “herd immunity” threshold; almost all age groups had seropositivity rates for measles antibodies over >95%, and;

Data on laboratory testing and case investigation performance indicated that US surveillance adequately and quickly identified measles cases and transmission chains, meaning high-quality surveillance occurred during the study period.

2018-2019 New York measles outbreak

Before 2025, the largest outbreak of measles (1,249 cases) since the 2000 US elimination was one in 2018-2019. In late 2018, internationally-imported measles cases ignited a large outbreak clustered in a number of tight-knit communities with low vaccination rates in New York City, as well as surrounding counties (most notably, Rockland County). State and local officials implemented public health measures to fight the outbreak including: declaring a public health emergency, mandating vaccinations, and collecting fines from parents who did not vaccinate their children. This led to 60,000 MMR vaccine doses being delivered in the affected areas. The officials led strong communication and outreach efforts. Health officials also closed schools where measles outbreaks occurred, prohibited unvaccinated children from attending school.

In 2018 through 2019, the CDC provided technical assistance and support to New York, and made clear, positive statements about how vaccinating against measles is important. Then-CDC Director Robert Redfield stated: “I encourage all Americans to adhere to CDC vaccine guidelines in order to protect themselves, their families, and their communities from measles” and that “organizations had been deliberately targeting these communities with inaccurate and misleading information about vaccines.” President Trump agreed, stating “vaccinations are so important” and encouraging parents to vaccinate their children against measles. This kind of federal support, rhetorically or otherwise, is strained, at best, in 2025.

As a result of dedicated public health work, the New York outbreak was contained in less than 12 months, with transmission being considered interrupted by August 2019. Therefore, US measles elimination status was threatened that year, but not rescinded due to successful public health intervention.

Data Collection

The 2025 measles data in this review is sourced from the US CDC, here. It includes health data through October 21st, 2025.

The 2001-2011 measles data in this review is sourced from US CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), Division of Viral Diseases, here (download). It includes health data through September 30th, 2011, although provisionally reported measles cases through December 31st, 2011 are mentioned.

The 2018-2019 measles data is sources from US CDC’s MMWR, here.

Results

Comparison of first 10-months 2025 metrics to 2001-2011 US measles elimination study period metrics

As previously stated, the US has reported more cases of measles, 1,618 confirmed cases as of October 21st, this year than any year since 1992 (end of year 1992 total cases was 2,200). Although many of these US outbreaks began with imported cases (only 23 of these 1,618 cases were reported among international visitors to the US), a higher percentage of cases this year resulted from domestic transmission than importation than previous years. Additionally, US MMR national vaccination rates in recent years have declined below the herd immunity threshold goal of >95%.

Compared to the 2001 to 2011 elimination period, all 2025 metrics (number of total confirmed cases, confirmed measles cases in different states, number of outbreaks, percent of cases imported versus domestic, number of hospitalizations and deaths) are worse. In the 2001 to 2011 elimination period, 64 outbreaks occurred over a decade — 43 outbreaks occurred over 10 months of this year. In the 2001 to 2011 elimination period, 40% of cases were imported (60% domestic transmission) — in 2025, only 12% of cases were imported (88% domestic transmission). In the 2001 to 2011 elimination period, one measles death occurred — in 2025, there have been three deaths.

Comparing the first 10 months of 2025 to the 2001 to 2011 metrics, I get these results:

As of October 2025, there are greater than one reported measles cases per 10 million population — there are ~46.6 measles cases per 10 million people (number depends on 2025 US population estimate, this is for 1,618 cases per 347.3 million people);

As of October 2025, the majority (>50%) of measles cases were not imported and most imported cases did lead to further US spread — only 12% of cases were imported over the 10 month study period;

The number and size of measles outbreaks over that period were large (small outbreak defined by less than 5 cases): a total of 43 outbreaks in one year, with a median estimated outbreak size, based on available data, of 15.2 cases (Author’s note: this is a highly uncertain estimate based on what data was available from each state or jurisdiction — a limitation. The median number of cases could range from 3 to 16, or more. Feel free to estimate yourself. Note that for some outbreaks, such as the Texas outbreak are extremely large, with 762 cases). A few outbreaks included more than 100 cases, and the estimated median outbreak size is over 10 cases;

Measles vaccination rates among children were not sustained at high levels (>95%) over the study period, with the national kindergarten MMR vaccination coverage at 92.5% in 2025. In 2025, there are also significant differences in coverage by race/ethnicity, such as disparities affecting minority groups including Black and Hispanic/Latino children. These disparities are due to socioeconomic limitations, education levels, cultural and information barriers, and disparities in the quality of prenatal healthcare received. Vaccine coverage is also low among some religious groups due to religious exemptions, both historically and in 2025, with such groups driving some of the larger 2025 outbreaks due to their largely unvaccinated, close-knit populations.

For national survey data, official 2025 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data is is not yet available on whether population immunity to measles was above the “herd immunity” threshold (NHANES data are collected over a two-year period, a new cycle began in early 2025), although vaccine coverage is estimated above (see bullet 4) using studies, administrative data, and other household surveys; NHANES does not have available 2025 data yet on all age groups’ seropositivity rates for measles antibodies — a limitation, and;

There is limited publicly available data on laboratory testing and case investigation performance to indicate that US surveillance is adequately and quickly identifying measles cases and transmission chains, so there is a limitation in determining whether high-quality surveillance is still occurring during the study period — a limitation.

Comparison to 2019, a year of threats to measles elimination (New York)

Many data points this year are also worse than those from 2019, when U.S. measles elimination status was last threatened. For example, from January to October 1, 2019 (by which time the large outbreaks centered in New York had been contained), there had been 1,249 total measles cases, and 22 total outbreaks across 17 states; in 2025 those numbers have already been surpassed.

Conclusion

Based on past definitions and benchmarks used for determining US measles elimination, it appears that if current trends hold through the remainder of the year 2025 and into early 2026, US measles elimination status in the US may plausibly be rescinded after January 2026. This would be determined after the 12-month observation period of sustained transmission concludes, after January 17th, 2026.

Discussion & Limitations

State and local health departments are primarily responsible for measles outbreak response, with support from the federal government. Currently, programmatic metrics on state and local health departments’ measles prevention efforts (such as response times) and capacity (such as number of staff working on any given outbreak) are often not made publicly available, which means defining whether US surveillance is still “high-quality” is difficult. However, in 2025, state and local public health departments have faced significant funding cuts from the federal government in comparison to past years, which likely has impacted capacity to track and respond to outbreaks. In the recent past, the federal government has provided the majority of funds for state and local health departments’ budgets. NHANES 2025 data on all age groups’ seropositivity rates for measles antibodies is also not yet available. The estimated median number of cases for the 2025 measles outbreaks is also based on currently, publicly, available data. The availability and timeliness of these data varies greatly by state or jurisdiction, making this number highly uncertain.

The states most affected by measles outbreaks in 2025, such as Texas, New Mexico, and now Utah and Arizona, have not taken the actions New York did in 2019 (such as local vaccination mandates, school attendance limitations, and fines). Although CDC has provided technical assistance and funding support for outbreak epicenters, the HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. has understated the health risks of measles infection. He has also made mixed, leaning toward negative, statements in the past about the importance of vaccination. Another example in addition to his statements in 2019 about Samoa is his and other Trump health officials’, and President Donald Trump himself, recent focus on separating out the vital MMR vaccine into three vaccines, which would likely increase opportunities for infection if not taken simultaneously and could potentially affect insurance coverage of either the combined or monovalent vaccines, especially low-income children in special programs such as Vaccines for Children (VFC), decrease overall access to these vaccines for working class families due to possible increased doctor’s visits and related fees, increase distress for children getting vaccinated, among numerous other limitations, such as lack of market motivation to develop and roll-out monovalent vaccines for these diseases in the US — reasons which are often scoffed at, which makes me crazy (Author’s note: this is probably the first MMWR-inspired publication to have a bit of editorialization, sorry. I am mad at people manufacturing consent for this unnecessary move that puts children’s health at risk. People are currently, and historically, doing so likely for profit and ego). RFK Jr. has instead encouraged what he deems to be “alternative treatments,” such as treating measles with vitamin A supplements rather than preventive vaccination, which has resulted in hospitalizations of children for vitamin A toxicity from overdoses.

Additionally, as mentioned earlier, national measles vaccination has declined over the past half-decade, with childhood measles rates dropping below the 95% threshold. Some public opinion polling has shown that parents are frequently exposed to medical misinformation about measles and the MMR vaccine, with nearly 20% of US adults in 2025 responding that they believe the false claim that “getting the measles vaccine is more dangerous than becoming infected with measles” (poll respondents selected “probably” or “definitely true” for this statement).

Recommendations & Implications for Public Health Practice

I recommend a reversal of cuts in staffing and funding for local, state, and federal public health departments, as well as Medicaid, Medicare, and threats to Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies (i.e., reversing of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA)’s stricter verification requirements for premium tax credits, which may end automatic re-enrollment for many and require manual verification for new enrollees); a societal re-dedication to elimination and vaccination campaigns dedicated to achieving the >95% two-dose measles vaccination herd immunity threshold goal; and increased health education on measles and vaccination. I additionally recommend the resignation of RFK Jr. from his position as HHS Secretary for his promotion of misinformation about measles and vaccines.

If US measles elimination status is rescinded after 2025, I recommend the default re-observation of 12-months’ data following the recension, during which public health interventions that have previously been successful are used such as: declaring public health emergencies in affected areas; vaccination mandates for public spaces and institutions, i.e., schools, which includes informed consent; closing of affected schools until cases subside; fines for parents not vaccinating children against measles prior to school enrollment and attendance; and limitations to school attendance based on vaccination status.

Authors

Miranda M. Mitchell, MPH

Credit for aggregation of many of the sources and information used in this article goes to this KFF article.

Publication: Wauneka Health will cover emerging public health topics in the US and globally, aiming to resist Trump’s anti-science agenda and provide credible health information during the current “information blackout” caused by government and academic funding cuts. The newsletter is named to honor Annie Dodge Wauneka, “The Legendary Mother of Navajo Nation,” an influential leader of Navajo Nation on the Navajo Nation Council. Wauneka grew up during the 1918 Spanish Flu and saw how it ravished her community. In particular, she observed how the language barrier between Navajo and United States public health workers lead to cases being overlooked. After this pandemic, she dedicated her life to improving her Nation’s public health outcomes and related health education, becoming the three-term head of the council’s Health and Welfare Committee. She is known for her focus on eliminating tuberculosis in her Nation — vowing to not repeat the failures of the Spanish Flu during the early 1950s tuberculosis epidemic in Navajo Nation, Wauneka authored a Navajo (Diné bizaad) dictionary for English medical terms. This dictionary contributed to a 35% drop in tuberculosis infections by 1970. In 1963, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Lyndon B. Johnson, as well as the Indian Council Fire Achievement Award and the Navajo Medal of Honor. She holds an honorary doctorate in public health from University of New Mexico and was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Miranda chose to honor Wauneka not only for her impressive achievements in public health, but because of Miranda’s personal connection to the Navajo people after having the honor of serving with them as an assistant tribal liaison during the COVID-19 pandemic. More on Wauneka here.

Author: Miranda Mitchell, MPH (“Roo McGuire”) is an environmental health scientist. Opinions are her own and do not represent the institutions she was previously affiliated with. She is a graduate of Emory University and Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, as well as former intern at the Office of Children’s Health at US EPA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., graduate work-study at US CDC Headquarters at its Roybal Campus in the National Center for Emerging Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) fellow and full-time employee at US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) at US CDC’s Chamblee Campus. Her Master’s thesis, published in Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID), investigated the potential transmission dynamics and genetic diversity of a bacteria in bats and their ectoparasites. Her areas of expertise are health risk assessment, environmental health science, molecular biology, and infectious disease epidemiology. She currently makes public health and political educational content here and on Twitch.tv/roomcguire, while she awaits her first child and hopes to pursue a doctorate sometime after 2028. She has never received any money from pharmaceutical companies and declares no conflicts of interest.